SELMA PARLOUR

paintings |

installation views |

about |

cv |

contact |

|---|

Selma Parlour's meticulous oil paintings appear as though they're drawn, dyed, or printed. Alongside her delicately-shaded bands and pencil-thin (oil-made) lines, colour is a veil (not a skin) imitating the backlit quality of the screen and ensuring that every decision is evident. The London-based artist is known for her units of luminous colour, diagrammatic space, codified illusion, haptic surfaces, and her abstract-paintings-of-photography's-installation-shot-of-abstract-painting. |

|---|

Selma Parlour (British, b. 1976, Johannesburg, South Africa) received her practice-led PhD in Art from Goldsmiths, University of London in 2014. Awards include an Abbey Fellowship in Painting, the British School at Rome (2023); an Arts Council England Creative Development Award (2020); the Mark Rothko Memorial Trust Artist-in-Residence Award (2018); the Sunny Dupree Family Award for a Woman Artist, the Summer Exhibition, the Royal Academy of Arts, London (2017); and the John Moores Painting Prize (prizewinner, 2016). Other notable awards are a runner-up award from the Arts Foundation (2014); Thames and Hudson’s international competition and publication ‘100 Painters of Tomorrow’ (2014); and New Contemporaries, ICA London (2011). Solo exhibitions are: 'Salon Paintings', Almine Rech, Paris (2023); 'Yonder Cloud', Pi Artworks, London (2022); 'Warp & Weft', Dio Horia Acropolis, Athens (2022); ‘Selma Parlour’, Pi Artworks, Istanbul (2020); ‘Activities for the Abyss’, Pi Artworks, London (2019); ‘Upright Animal’, Pi Artworks, London (2018); ‘Parlour Games’, a site-specific installation with Marcelle Joseph Projects, House of St Barnabas, London (2016); ‘Paradoxes of the Flattened-out Cavity’, Dio Horia, Mykonos (2015); and ‘Selma Parlour’, MOT International, London (2012). Recent group exhibitions: 'Unreal City', Saatchi Gallery, London (2024); 'Gesture and Form', Almine Rech, New York (2024); and 'Feeling of Light', Almine Rech, Brussels (2023). Collections include the Saatchi Gallery, and Christian Dior Couture. |

|

|

|---|

ES magazine, 2019 |

The Times, 2016 |

|---|

In delicate, precise paintings referencing iconic architectural geometries, Parlour's canvases are cosmic windows that compress time to merge the forms of present and past. – Cathryn Drake, Artforum, 2015 |

|---|

Parlour's paintings carry colour without volume. Maintaining a relation to printmaking, the build-up is tonal, stained, almost as if in a photograph, with the sense of hands off as well as hands on. A layered levelling of colour, where the artist appears to have pulled the canvas, as if a shroud, out of liquid in a gesture of reversed negativity. Material is born from light, which attaches and embeds itself on the surface and, yet, something seems to permeate from behind. Paint, as material, has been banished from view to become a layered, thinned, subliminal notion. Diluted and dilated, it has long been absorbed into the thought process of the artist. [...] Colour lies in an afterglow or in an echo of something seen more than once and remembered. Layers of colour pool at the literal edge. The quality of grey, blue or purple carries great intelligence, for it seems to have arrived in this world fixed and not worked out through any apparent process of mixing. Parlour's repetition of vision allows calm understanding rather than any anticipated experience. A range of associations must be indulged; the relation to print must be understood. How does the graphic quality of the 20th century transport itself to now? [...] Classic trompe l'oeil is about shallow space, the repository for idea and thought. Parlour allows, with finesse and attention, the tooth of the linen to become the actual beat of the moment and detail; she uses cross weave as pixelation. While sight knows and shifts, the grain of the surface resonates with an unconscious understanding. [...] Parlour has, through her fascination with installation and context, moved between asking the work to inhabit real space – in order to continue the metaphor, style, emphasis, and manner of a particular context – and expecting the work to provide its own place, architecture and context. The role of this fluidity in Parlour's work extends further than Rothko, for instance, aware of the fact that his paintings would be the main feature of an expensive restaurant, or Léger, who had planned a chapel all along. It is not what the paintings lend a place that Parlour is concerned about, but what they project onto it or draw back towards themselves. – Sacha Craddock, 2018 |

|---|

Selma Parlour opens painting up to other hypotheses, to that of a haptic serenity where light, finding refuge in the material, unfolds an interweaving of subtle associations that draw the eye into a meditative plunge. Committed to questioning the foundations of her medium, the British artist has developed a singular pictorial vocabulary in which the language of geometric abstraction blossoms in works with a diagrammatic aesthetic. Obtained by the meticulous addition of thin oil washes on linen canvases, her painted works, at once delicate and translucent, take on the appearance of drawn or printed surfaces that tend towards the subliminal. Caught up in a contradictory movement of sedimentation and expansion, paint becomes a source of light, stratifying and liberating itself to reveal all its depth and radiance. – Maud de la Forterie, 2023 |

|---|

The work in this show is quiet, contemplative and often very satisfying. Take Selma Parlour, for instance. Painted in thin washes of oil on linen, Room consists of a nest of squares flanked by trapeziums to create an illusion of depth, while acknowledging the flatness of the canvas. It allows the picture to be read as a flat surface, a box, a truncated pyramid or all three. The game is as old as painting itself, but Parlour’s handling is perfect. A series of extremely subtle colours have been applied with the exactitude of an illuminator decorating a manuscript. The results are as pleasing as a perfect equation and the acronym QED (quod erat demonstrandum), usually appended to the proof of a theorem, would not be inappropriate. – Sarah Kent, The Arts Desk, 2011 |

|---|

While I love the candy coloured, hard-edged but softly tempered world of abstraction she often delivers us into, it's the monochrome works in the mix that pull me in. The artist's hand-engineered but could-be-digital-at-distance techincs push umber tones to the limits of existence on canvas. Spread thin, sample on slide and from dark to light, they articulate mirror-like composistions devoid of any actual reflective properties. Yet, somehow - in ways that avoid the theatrics of the echo chamber - they remain defiantly two-dimensional. We are left hovering between matter and fact in a quasi-real space ripe for poetic projection. Beautiful visual condundrums that defy expectation. – Apple and Hat, 2022 |

|---|

Reading Eleventh Hour Squared III, 2016, as a flat surface becomes more difficult the more that shadows are perceived and the more the luminous blue square is perceived as sky through a window pane flanked by a brown frame, the primary image that I keep settling upon, until the pyramid reasserts itself. But then I am puzzled by the sense of this being a corner or a quadrant. In what context might one see only this part of either a pyramid or a window? Photography comes to mind, the camera frame characteristically cropping objects in this way. And there is something about the colour quality, thinly applied hues, with the white surface behind giving them brilliance, which is reminiscent of a photograph or a computer screen. The paint application, transparent films of oil paint, with no visible traces of the artist's toil, also lends itself to this interpretation. If photography is 'drawing with light', then Parlour's paintings are closely akin to photography. However, they are ultimately abstract because figurative interpretations, like the ones suggested above never quite work enough to arrive at definite conclusions. [...] In Parlour's work it is as if |

|

Eleventh Hour Squared III |

|---|

the hint at referential content is always self-referential, always bringing us back to the painting itself. There may also be references to the history of abstraction, specifically post-painterly abstraction, or colour field painting, if not in the scale of the works, then in the artist's choice of technique, in which the method of production is hidden by the method of production itself, the labour painted out or sublimated. – Andy Parkinson, Patterns that Connect, 2017 |

|---|

Parlour paints with thin films of oil on linen, using the technique to play with depth and texture. The result is an illusory, trompe l'oeil-like effect that works against the eye's instinctual efforts in finding points of focus. All paintings need to be seen in person to be properly appreciated, of course, but that's especially the case with Parlour's work, which purposely subverts the optics of a camera lens. [...] "Selma's brilliant in terms of talking about the relationship between painting and the academic approaches to it," says Sacha Craddock, who curated the show. "That's very unusual. I've always found that academics make really bad work because they talk too well about it. She's an exception to that rule." Craddock, who also curated last year's Turner Prize exhibition, met Parlour through the 2011 New Contemporaries show, an annual exhibition of the best work coming out of art schools, for which Craddock is both the chair and head of the selection process. "I remember thinking how intelligent it seemed," notes Craddock. "When I looked at her work it wasn't that I was thinking about her relationship to the history of painting—that came later. I just saw a very interesting use of the shallowness of space that lent it an associative, illusory possibility, and a sustained relationship to abstraction that wasn't absolutely about the rigors of abstraction." – Taylor DaFoe, Artnet News, 2018 |

|---|

This is a show that releases both dopamine and mild anxiety, thanks to the pleasure of the warm hues, and the stress caused by an indeterminate focal point. The London-based painter has laid claim to a palette of lively yet soft colours in which gray-mauve and burnt ochre both stand out. Further striking moments are provided by electric blues, a deep turquoise and a treacle-like golden yellow. Just a stone's throw away on Oxford Street, the shop-window dressers offer less incongruous pleasures. You might conclude that Parlour's colours are neither fashionable nor seasonal. As a serious painter, it must take effort to avoid being either. – Mark Sheerin, The Arts Desk, 2018 |

|---|

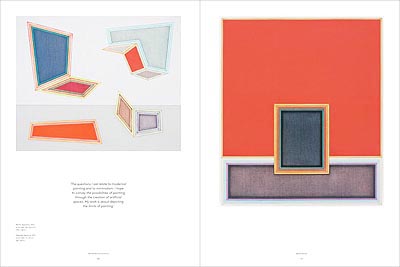

At first very little of the human is visible, but on closer inspection there are many signs of the artist's hand – in degrees of shading, playful acceptance of some accidental-looking effects, and the variable overlapping of veiled layers. Far from being mechanical, the transparency of Parlour's technique actually reveals the decision-making in her process. Then there's the back and forth between abstract and figurative. Previously, Parlour's work has looked like paintings of paintings installed in ambiguous spaces – meta-painting of a sort. This body of work seems to have zoomed in on the frames of those paintings so that they look – somehow – both more representational and more abstract: more representational through the suggestion of such architectural details as mouldings or cornices; more abstract, as 'complete shapes' [...] A sub-plot to that abstract-figurative ambiguity is how some edges are 'clean', as one suggested plane abuts another; while others are 'dirty', with smudges of what might be shading. Is the difference representational, indicating the depths of three dimensional planes? Or are those contrasts decided by what works in abstract terms? [...] Screen and architecture are, of course, very |

|

Compile time IV |

|---|

different spaces – and different again from the literal flatness allied to implied space of the painting itself. That may well be Parlour's primary to and fro – between the wall and the painting on it, the illusional space and its denial; between how the paintings read spatially if taken as abstract, or if as figurative. And then we have to consider that these paintings of possible architectures are placed in a real architectural space with which they interact in turn... There's also a back and forth between part and whole. Parlour's previous use of what could be images of full frames is now merely implied by what look like photographic crops of them. Complicating that, the Compile Time series are divided into sections of up to four parts, crisply enough to make me wonder whether they were conjoined sections. That turns out to be a faked move, but one which ratchets up the dialogue between part and whole. The paradoxical idea comes to mind that these paintings are details of themselves: rather as Magritte claimed 'this is not a pipe', Parlour might be claiming, in an attractive contradiction, that 'this is not a complete painting'. As Andy Parkinson has put it "the hint at referential content is always self-referential, bringing us back to the painting itself". That paradoxical aspect is, I think, where |

|

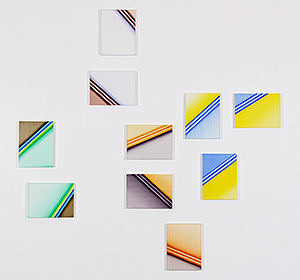

Detail Shot Series, installation view |

|---|

Parlour is at her most original. The other ambiguities have been more widely explored, and are perhaps most notably exploited and subverted in recent practice by Tomma Abts, with whose work Parlour's has much in common. That said, Parlour explores and combines those concerns in her own way and with seductive intelligence. There is plenty here for eye and brain. – Paul Carey-Kent, Saturation Point, 2018 |

|---|

The inviting, yet ultimately impenetrable nature of her compositions keeps the eye moving across the surface of each canvas. In the hunt for visual entryways, through the implied sense of multiple spaces created, we become aware of the extrordinary details: the processes that allow paint to convey qualities of many other material and archi-spatial properties. As a viewer, there is a real sense of being manipulated, siren-called into vistas that so nearly become places open and accessible for projection, only to be kept at the treshold. But the notion of a limited view is entirely tempered by the surface intricacies; we are happy to be implicated in such a visually rewarding and purposely game-like strategy. – Apple and Hat, 2021 |

|---|

Her delicate shading can only hint at depth, and heighten the intensity of the jewel-like works. She layers her paint with great patience and skill to achieve a luminous ground, with as much light trickery as a Van Eyck or a Rothko. As a result her colours punch out, in a wild range of shades from pretty pastel to harshly acidic. [...] Parlour's highly technical, lexical, and at times abstruse works are much more challenging than that last viral tweet you saw. – Mark Sheerin, FAD magazine, 2020 |

|---|

Selma Parlour’s haunted paintings hover with retinal disparity across the space. The luminous synchronicity, in this case, operates through our intrusion into a private world, where a parallel dimension may exist. The colour shifts in the multiple framing of each composition are exact, and build a system that is modulated through the tonal colour bleeds. In One for each eye 4, each successive colour - cobalt violet, manganese blue, viridian green and brown /ochre - alter the perception of the retinal spatialisation. Here the space between the eyes, which allows binocular vision (the angle from which each eye views an object) creates the imperfect match with its counterpart, a yellow multi-toned field of colour. These paintings are shimmering, intense objects, and their emptiness allows the other works in the space to breathe. – Laurence Noga, Saturation Point, 2016 |

|---|

On entering this year’s prize, we are met with a small but powerful painting, One, The Side-ness of In-Out by Selma Parlour, dominated by architectural language. Parlour presents an ambiguous, graphic scene that could be interpreted as looking through a segmented frame. Formally it is reminiscent of skirting boards and cornicing, suggesting diverse origins such as Victorian architecture and modern high rise buildings. Shapes are very clearly delineated in a limited, bold colour palette, with little evidence of brushstrokes, with a smooth, flat surface through layers of glaze. This smooth exterior contributes to the ambiguity in the work, as we are left wondering if the frame is a window, and how are we positioned in relation to it – is it a room or gallery, a street or square? – Jenny Steele, A-N, 2016 |

|---|

Parlour begins with colour, her use of thin, transparent glazes allowing the woven surface of the canvas to remain visible, whilst giving the work an inner translucent glow. The division of the canvas horizontally creates an horizon line to suggest distance and space. This sense of depth is reinforced by the shadowy smudge that shades each of her lines. Along the top and right hand edges a broad blue frame holds the space in and flattens it out, creating the impression of a painting within a painting. But the frame is incomplete, and the two diagonal lines that terminate each side converge towards a vanishing point, turning the frame into a proscenium arch and the painting into a stage. The actors on this stage, or the subjects of this painting, are two four-sided shapes: a trapezium, whose converging sides draw the eye in, and a quadrilateral, which seems to fold over towards the viewer. The trapezium appears flat, the quadrilateral freestanding and solid. They reinforce the sense of three-dimensional space, but they also disrupt it. [...] Parlour's pictorial space is impossible. It breaks all the rules and confounds all expectations, demanding to be read from multiple perspectives rather than a single viewpoint. – Richard Davey, John Moores Painting Prize, National Museums Liverpool, 2016 |

|

One, The Side-ness of In-Out |

|---|

Selma Parlour's oil painting 'One, the Sideness of In-Out', 2015, painted on linen, also echoes the surrealists: Magritte's Strange interiors; Chirico's blue/orange contrasts, for example. It is fairly uncomfortable to look at, being small and a bit cluttered and it engages the analytical mind [...] in a futile attempt to make sense of our perception: the mismatching sides, the folding in at the bottom right hand side; the in-outness. Our edgy attempt to impose perceptual equanimity is hereby challenged. – Sandra Gibson, – Sandra Gibson, Nerve Magazine, 2016 |

|---|

The spaces Parlour creates in her compositions initially appear ripe for mental projection, but actually serve to thwart our ocular need to move through the plane, or locate ourselves within the image by way of secure structural elements. Rather, they deliver a sense of contrary delight, at being prettily slippery and defiantly two-dimensional in an increasingly screen-based world. – Apple and Hat, 2019 |

|---|

It is a testament to the authority of the medium that sometimes the most minimal paintings are the most powerful. [...] Parlour draws upon a rich lineage of mimimalist art. [...] Her delicate, translucent painting offers a suggestion of a back-story for each work, tantalizing the viewer with withheld information. This notion is crucial for Parlour who considers illusion and the limitations of painting to be central themes in her work. [...] The simultaneous creation and negation of space are significant in Parlour's work. Through geometry and isolated two-dimensional forms, she crafts stage-like settings that mingle foreground and backgroud and imbue a sense of spatial confusion. Her interest lies in 'painting that questions its historical constraints to re-frame itself through invented vocabulary and abstract space'. However, her artificial spaces hold more than mere aesthetic interest; they are a means through which Parlour can emphasize the greater possibilities of painting as a tool for interrogation and communication. – Kurt Beers, 100 Painters of Tomorrow, Thames & Hudson, 2014 |

|---|

|

|

|---|

© Selma Parlour 2024 |

|---|